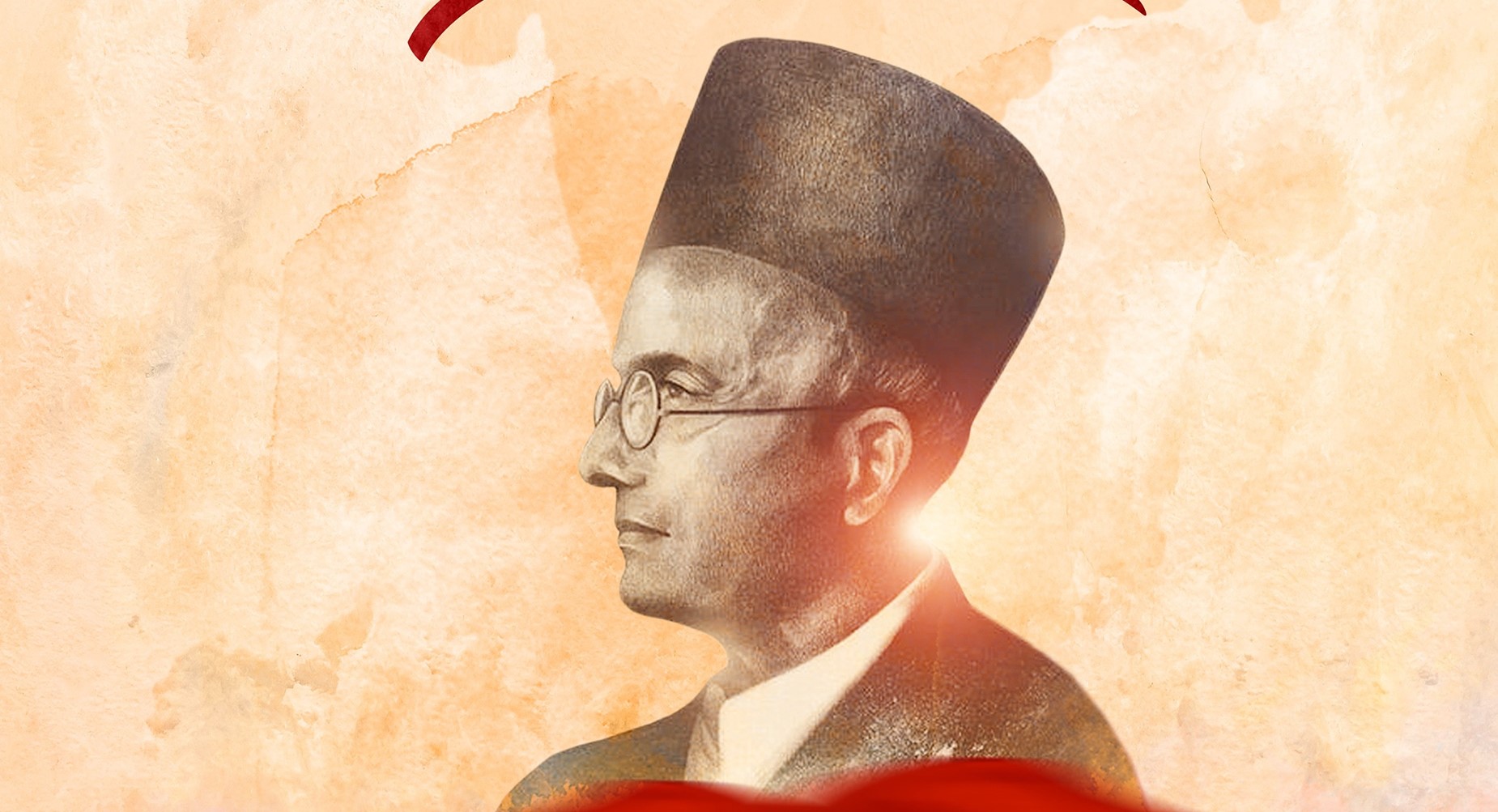

The eclipse of Nehruvian modernity has given rise to an assertive Hindu modernity which has animatedly replaced the former. It is henceforth unsurprising that the vociferous votaries of Hindutva champion modernity today. It is veraciously proclaimed with an intense exuberance that Hindutva stands for Hindu modernity. This sort of modernist zeal propounded by adherents of Hindutva belies the belief held by Indian progressives who abhor Hindutva for its alleged sins of casteism and sexism and both addled by communalism; the original sin in the Indian progressive mythology. The Hindu modernist who wears Savarkarite variety of reformist tendencies on his sleeves is condemned often in some traditionalist circles who accuse them of being a liberal hiding in the saffron wool. These Hindu Traditionalists who are either sceptical or the silent supporter of Hindutva are yet to embark on the quest to wrestle Hindutva from Hindu modernists. Their qualms with Savarkar are fixated on the central question of reform vis-a-vis the thorny questions of caste, Hindu family, marriage, women, conversion and cow. In the previous piece, we explored whether the possibility of Savarkar’s thought to align with conservatism exist, this piece lends firmness to the seemingly novel idea in affirmative.

Savarkar's fanatic efforts to bring the reforms in the Hindu society and its outdated institutions is a source of vicarious joy for the Hindu modernist creed. The Hindu modernist rejoices at the prospect of atoning sins which he perceives his ancestors had committed for continuous centuries on the lower caste Hindus. He is inclined to forget in his rejoicing that Savarkar could not be a partisan of any particular caste nor could he stall his criticism for what he believed was committed and perpetuated by entire Hindu society. His biting and stinging criticism is patriarch - alike; an admonishment and reproach to Hindus for their own sake.

The uneasy terrain of reform that Savarkar undertook in Ratnagiri while being confined constitutes an essential chapter of Hindutva in action. Ratnagiri exemplified what the Hindutva project wanted and worked collectively to achieve. Ratnagiri could be heralded as a Hindutva laboratory under the technician vision of Savarkar. His support for intercaste and widow marriage through the arguments framed outside the traditional bounds, decisively defying the sanctified authority of Shastras makes him a reformist par excellence. His utilitarian attitude vis-a-vis cows, his deliberate desacralization of cows from the aura of holiness that is associated with what traditional Hindus consider as Gau-mata( mother cow) would only be considered as offensive, if not downright repulsive. And yet, Savarkar occupies a place of central importance in the Hindu pantheon of personalities.

The lamentations of Savarkar in his last major work ‘Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History’ have been scrutinised not very often as much as his pronouncements of victorious Hindu rulers. Many have failed to decipher that within these pages the maker of Hindutva wails over and over again about defects of Hindu society that has constantly led to their downfall in numbers. Savarkar’s refrain is acutely visible in his writing on Tipu Sultan. He recounts how Tipu converted millions of Hindu men and women. He is assured of the prospect that “all those two or three hundred thousand Hindu men and women recently converted” wanted to re- convert “because of the love they bore for their original families and relatives, and because of the pangs of separation they suffered.” He bemoans how after the death of Tipu, Maratha army lost the opportunity to convert back those Hindus:

Neither those Maratha warriors, nor their commanders, nor the Sardars and Chieftains nor the Shankaracharyas, nay not even the Peshwa at Poona, nor the Chhatrapatis of Satara and Kolhapur- alas! not a single Hindu soul ever dreamt of this simple way of reconversion of those ill-starred Hindus! Nobody of them ever felt ashmed of marching straight ahead, without casting so much as a sympathetic glance at the thousands of the brutally ravaged Hindu mothers and sisters!

Savarkar's indictment was that only political victory was not enough but it was just a means to secure far broader cultural ends which had to be done without being afflicted with the perversion of virtues. Savarkar is most critical of the fact that how the foolish bans on reconversion led to the vast growth of Muslim population who bore hatred for Hinduism. The dwindling demographics due to religious conversions had to be countered. Savarkar observed:

Even in those days, the Hindu society was quite aware of this numerical loss! But because of their morbid ban on reconversion, no effective remedy could be found against this drain of its lifeblood. Very like the invalid patient, meekly bearing the death-pangs of an incurable disease, the then Hindu world endured this blood-draining, deadly disease!

For Savarkar Shuddhi fulfilled an essential ambition of Hindutva; maintaining the demographics of Hindus as a majority. He strongly believed, in the words of Vaibhav Purandare, “there was no alternative to the campaign for shuddhi if Hindu society were to retain its identity and character in the face of what he saw as Islamic aggression.” His discernment and prudence in his support for Shuddhi makes him a visionary in his own right and the partition substantially vindicated his position where minority Hindu population areas in West and East parts of India were forcibly taken away by the predatory forces of Islamism.

Even progressives of today despite being faced with the plethora of historical incidents that resemble pre-partition era only scoff at any mention of dwindling numbers of Hindus. They are horrified to hear about the Ghar Wapsi (modern day shuddhi movement) campaigns. Any murmur of demographics is taken as an evidence of communal fear mongering. Any historical precedent has to be sidelined, obscured and eventually forgotten.

An another recurring theme in Savarkar's life is his lifelong opposition to the vivisection of India what he called fatherland and holy land of Hindus. He considered loss of Hindu lands “graver still than this loss of numerical strength”, as it led to “ the permanent loss of the vast territory snatched away by the Muslim religious incursions” gradually “without the knowledge of the Hindus!” Savarkar is preoccupied with “this loss of numbers and territory that the Hindu nation had to suffer because of the morbid Hindu religious concepts of various bans and their perverted sense of virtues!”

These two major preoccupations of Savarkarite project, loss of land and numbers, which are essentially conservative in their nature had to be dealt with any means, it could mean the removal of any particular disability that threatened to block his Hindutva project. Savarkar's progressivism is ultimately derived from the sentiment of conserving and consolidating Hinduism in India.

Savarkar's work of Hindutva stemmed, atleast in parts, from the Khilafat movement. He could sense how religious loyalty of Muslims had almost made it impossible for them to participate in the Indian National movement. This viewpoint was expressed earlier even by moderates like Surendranath Banerjee who castigated Muslims for working “in opposition to the national movement” and G. K. Gokhale who frankly said that “seventy millions of Muhammadans were more or less hostile to national aspirations.” The support for Khilafat movement by Mahatma Gandhi deeply troubled Savarkar who foresaw that it will foment separatism and fanaticism more amongst Muslims. Savarkar acutely captured the anxiety of those Indians who wanted the ideal of fraternity but not by dissolving their nationality and substitute it for Pan- Islamism. However for Gandhi, Khilafat and Swaraj were interconnected and only by supporting Khilafat, Hindu - Muslim brotherhood could be achieved. Gandhi's acceptance of Pan-Islamic movement as a necessary condition for Hindu-Muslim unity constitutes a deeper conviction held by secularists to this day that without obeisance to Islamic Ummah and loyalty to Islam, Hindus cannot purify their bigotry from the muddy waters of communalism.

Savarkar also noticed the pronouncements of Muslim leaders who had no qualms with inviting foreign armies of Islam to invade India in the Khilafat movement. The Moplah carnage where hundreds of Hindus were murdered strengthened his belief that Khilafat movement was a folly of high magnitude which intensified the extra- territorial allegiances of Muslims to the far away land of Turkey and Arabia. Such injurious activities to Indian nationality needed a vigorous response; a response that aimed to secured the loyalty of all communities to the Indian nationality which was to be imparted in Hindutva terms where it shredded any theological connotation and assumed larger cultural significance. All communities were invited to participate in this alternative ideal of Hindutva fraternity which was eventually based on the “choice of love.” Savarkar is hesitant, if not suspicious of anything that “smacks foreign” and this underscores an important facet of conservatism which is often shy of accepting what is strange and differrent.

Here we can ascertain two central themes and major ends of Savarkarite conservatism: the preservation of numerical dominance of Hindu community in India and protection of this ‘holyland’ from the aggressive foreign monotheistic forces whose very ideology is based upon conquering the infidel lands.This is what Savarkar aspired to do as well with his support of Shuddhi and sanghatana(organisation) movements! The reformist outlook and the seemingly radical impulse in Savarkar springs from these core conservative concerns that occupied his whole life.

Edmund Burke, the father of modern conservatism, had written in precise terms: “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation. Without such means it might even risk the loss of that part of the constitution which it wished the most religiously to preserve.” Dr B. R. Ambedkar had used Burke's observations to bolster his arguments in his radical tract ‘Annihilation of caste’. He warned Hindus that if they wished to preserve Hinduism they have to get rid of caste.

The spirit of such wise words and arguments were apparently always within Savarkar who never shied away from warning Hindus about “a terrible crisis that will befall” on the Hindu community if they were reluctant to shed their old prejudices of untouchability against Shudras who “are going to come in very handy for our enemies, to divide and conquer” as “we have meted out inhumane treatment to them”.

Savarkar knew that if Hindu society has to withstand the onslaught of conversions that was organised by two agressive monotheistic religions driven with divine sanction, especially aimed at those castes placed lower at the social hierarchy who were most susceptible to the threat of conversions, he must exhort Hindus under one banner of Hindutva. His activities at Andaman Jail clearly elucidated this vision where he pushed the idea of Shuddhi (purification) which aimed to re- convert Hindus back into the fold of Hinduism.

The Sangathan and Shuddhi moments were indeed innovations for their times as Hindus were divided on the basis of parochial constructs of language, region, caste and sect with a very loose sense of Hindu identity. These progressive measures were only a design to secure much more conservative end; unity of Hindu society that could procure enough strength to defend the land and the numbers of their community. The non- Kantian rationalist in Savarkar is unafraid to give hand to any necessary means that could secure his end objectives.

The outer mantle of Savarkar might be one of progress but the inner core remains one that seeks to preserve his community, culture and civilization.

Here, we must return to the internal chasm between the Hindu Modernists and Hindu Traditionalists within the Savarkarite Conservative movement. While the churning of ideas and exchange of a healthy dialogue between both sides have unfolded to a remarkable degree in the last decade, it remains to be seen how both sides deal with their differences. While Modernists often have the habit of invoking liberation from the social structures(e.g.: caste) which they perceive have been nothing but oppressive, any whisper of liberation from religion has been largely an anathema to their beliefs. This alleged inconsistency is exploited by the traditionalist who is critical of the bland idea of the annihilation of caste. He admits that the caste system may have been a source of vicious harm but the solution is not to kill it, but remove the evils that have crept in. You don't cut off your neck if it is sore, you take remedies. So, where does Savarkarite Conservatism fall between the currents of modernity and traditionalism? The study of “means and ends” of his ideological project convincingly shows us that his legacy shall be, perhaps forever, torn between both sides and this moment of conservative churn must go on for now with Savarkar at its polestar.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!